By Olugbenga Adebamiwa ( Newspot Political and Social Analyst)

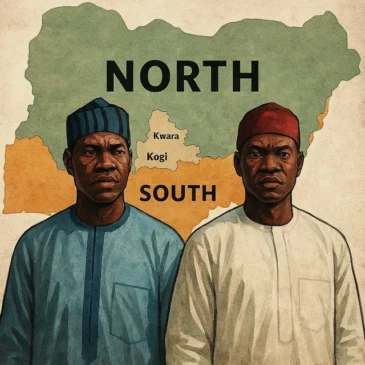

In Nigeria’s complex political geography, few regions embody contradiction like Kwara and Kogi States. Historically part of the Northern Region, both are home to large Yoruba populations who share cultural, linguistic, and ancestral ties with the Southwest. Yet, politically, they have long been absorbed into the northern fold, a legacy of colonial demarcations and post-independence realignments. The recent appointments of Bashir Bayo Ojulari (from Kwara) as Group CEO of NNPC Limited and Professor Joash Amupitan (from Kogi) as INEC Chairman by President Bola Tinubu have reignited old questions, are Kwara and Kogi truly northern states, or merely “southern enclaves” politically attached to the North?

The historical and administrative roots of this debate run deep. Kwara emerged in 1967 from the old Northern Region, while Kogi was carved out in 1991 from parts of Kwara and Benue. Both were placed in the North-Central geopolitical zone, a classification that was meant to reflect diversity but has since blurred their identity. The Yoruba-speaking populations of Ilorin, Offa, and Kabba have long considered themselves cultural cousins of the Oyo and Ekiti peoples, yet their political destinies have been shaped by northern power structures. The result is a region trapped between two spheres of influence, too “southern” for the North, too “northern” for the South.

This identity crisis has real consequences for governance and development. For decades, both states have complained of federal neglect, particularly in road infrastructure and security. The dilapidated Lokoja-Okene-Kabba-Ilorin highway stands as a grim metaphor for the disconnect, linking key Yoruba towns but largely abandoned by federal attention. In Kogi West, where the Okun people dominate, insecurity and kidnappings thrive along impassable roads, discouraging trade and agriculture. Many residents believe their classification as “northern” deprives them of the developmental focus enjoyed by southwestern states, while still exposing them to northern-style insecurity.

Tinubu’s appointments have, therefore, become more than personnel decisions, they symbolize a political reckoning. For the first time in decades, key national institutions, the NNPC and INEC are headed by individuals from these marginalized northern Yoruba enclaves. Supporters hail it as long-overdue recognition of forgotten constituencies, while critics frame it as a subtle extension of Yoruba dominance under the guise of inclusion. The truth likely lies somewhere in between. Tinubu, a consummate political strategist, may be using these appointments to expand Yoruba influence into the northern belt without overtly alienating the core North.

The North’s reaction has been telling. While some commentators, like Farooq Kperogi, have urged northern elites to embrace the appointments as proof of inclusive leadership, others see them as an erosion of northern unity. The debate reflects a deeper unease within northern politics, a fear of losing symbolic and institutional control. Yet, as history shows, the North was never a unified entity. From the Tiv of Benue to the Birom of Plateau and the Okun of Kogi, the northern identity has always been a political construct rather than a cultural constant. Tinubu’s appointments merely force that diversity into sharper relief.

For Kwara and Kogi’s Yoruba populations, however, the dilemma is fundamental. Decades of being treated as peripheral within both regions have fostered alienation. During Buhari’s era, their representation in federal appointments was minimal. Under Tinubu, visibility has improved, but questions linger, does visibility equal belonging? Or will these symbolic gestures evaporate once political tides shift after 2031? Many fear that once Tinubu leaves office, the fragile recognition they enjoy today could vanish, reverting them to their former invisibility within the northern establishment.

This debate also exposes a broader national hypocrisy. Ethnic appointments are criticized selectively, depending on who benefits. When Buhari appointed predominantly northern Muslims, it was justified as regional balancing, when Tinubu elevates northern Yorubas, it is condemned as ethnic domination. Both reflect a deeper failure of Nigeria’s federal character system meant to ensure inclusivity but often weaponized for political patronage. Unless merit, transparency, and equitable representation are institutionalized, such debates will continue to fuel resentment and reinforce regional fault lines.

In essence, the question of whether Kwara and Kogi are “northern” or “southern” misses the larger point. Nigeria’s problem is not geography, but justice, who gets what, and why. Until governance becomes genuinely inclusive, identity will remain transactional. The appointments of Ojulari and Amupitan, whether strategic or sincere, have at least reopened the national conversation on belonging, fairness, and representation. For the northern Yorubas, it is both an affirmation and a warning, inclusion is not a gift to be celebrated, but a right to be protected by the law.